The Coming Removal of the Mandate in China, Part 4: Oil

How China's legitimate need to bypass the Strait of Malacca will blow up in the CCP's face

According to the Law of the People's Republic of China on Guarding State Secrets, information regarding economic statistics within the People’s Republic of China is classified as State Secrets. While later laws such as the State Council of the People's Republic of China Decree No. 646, “The Implementing Regulations for the People's Republic of China Law on Protection of State Secrets", have urged local governments and the relevant Cabinet-level agencies of the PRC to divulge this information promptly - the fact remains that statistics such as information regarding how much oil is used by China is subject to control by the CCP.

As such, any statistics on Chinese oil usage presented here is at best incomplete and at best an educated guess.

That said, it’s good enough to let us get a general picture of how the CCP operates and the dire situation they face about national security and oil.

Statistics

The last year for which we have complete statistics which can be halfway trusted is 2016, via Worldometer.

Keep in mind that these are Pre-COVID numbers and do not take into account changes in consumption caused by the widespread lockdowns.

Information not on the table but which is available via Worldometer includes China’s 206 strategic reserve status: 25.132 Billion barrels of oil. This is sufficient for 5.4 years of consumption at current usage rates. Compare this to the 545.4 million barrels of oil in the US reserve as of May 4 according to the Department of Energy. This is sufficient for 2.9 years of replacement for oil imports.

When averaged out against the Chinese population, the People’s Republic of China requires an average of 3 barrels of crude oil per person every year - almost one-sixth of the US requirement of 20 barrels per oil per person per year.

However, this is peacetime.

Should China find itself in an all-out war, the PLA Ground Forces will require 35k tons of fuel every day simply for routine operations, with similar requirements from the PLA Air Force and PLA Navy. Per the information provided by James F. Dunnigan in the 4th Edition of How to Make War, this fuel requirement triples when on the offense, boosting PLA fuel usage from 115k tons during routine operations to 345k tons (2,360,206 barrels) per day China is on the offense. Factor in the 4 billion barrels of oil needed to keep the economy functioning and the weapons being produced, and the CCP’s reserves would be rather quickly tapped and her vehicles as stranded as those of Russia’s at the start of their invasion of Ukraine.*

*If you’d like to support the Ukrainian military, consider donating to the charity here, and get your custom message for the Russian troops committing genocide in Ukraine delivered to the Russian military at 2710 ft/s

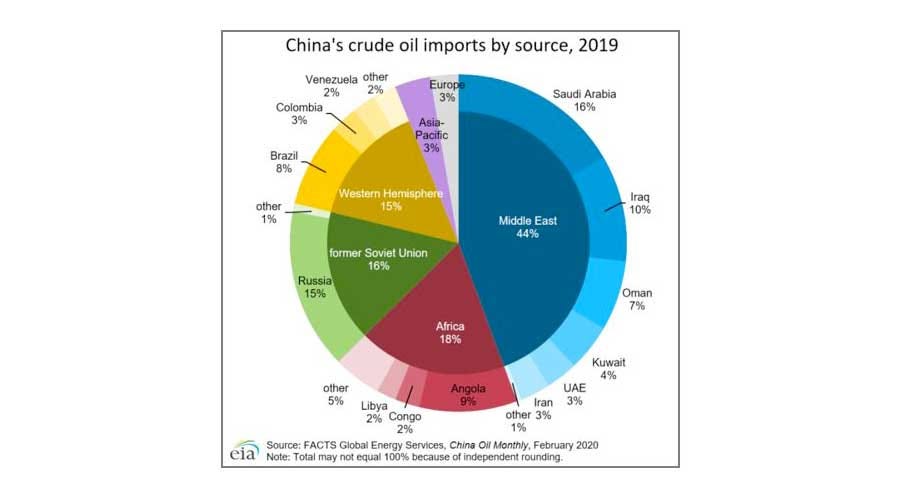

Pre-COVID, 44% of Chinese oil imports came from the Middle East, with an additional 18% flowing from Africa and another 10% coming out of the Atlantic or Caribbean Coasts of South America. This oil is largely moved via tankers through the Indian Ocean and into the Pacific.

This is where the Strait of Malacca comes in.

Strait of Malacca

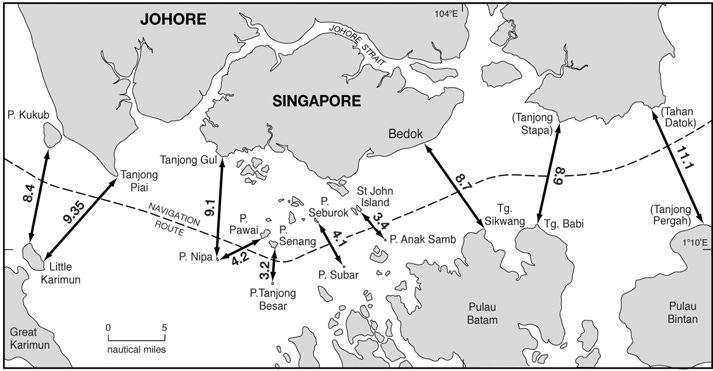

Located between the Malay Penninsula to the north and the island of Sumatra to the south, the narrow corridor is 930 km (580 mi) long with a width varying between 38 km at its widest and a mere 2.8 km at the Phillip Channel near Singapore. The Strait is so important to international shipping that it has given rise to a standard size for Very Large Crude Carriers (VLCC) known as the Malaccamax, with a draft of 20.5 m. Any vessel which requires more water below the sea level must divert south and east to pass between Bali and Lombok in the Lombok Strait - losing days and racking up the highest costs in fuel and wages for their employees.

This makes the Straits the single most important chokepoint for global trade as there are over 100,000 transits of the strait every year, averaging nearly 231 transits a day. This includes a full quarter of all goods transported via a Twenty-Foot Equivalent Unit or Forty-Foot Equivalent Unit container and a quarter of all oil bound for East Asia. The slow speeds at which vessels have to transit the strait and the prevalence of bad weather shutting down visibility (occasionally to the point the crew in the elevated bridge tower can’t see the bow of their ship) has also created a significant piracy issue.

To make matters worse, the congestion has resulted in several accidents and far more in the way of near misses between vessels weighing up to 250,000 tons and traveling at speeds of 18 miles per hour. If the worst happened and a disaster in the strait shut down transit the way the Ever Given blocked the Suez Canal, half of all global trade would have to be diverted to the Lombok Strait, which lacks the rudimentary traffic control present in Malacca.

Piracy and traffic accidents aren’t the only threat to travel through the Strait, though.

When China decided to encroach on Indian sovereign territory in Ladakh over the fact India was building out infrastructure in the Galwan valley to defend their territory from Chinese aggression, India dispatched a small number of warships to INS Jarawa as an implicit threat to close the Strait to all Chinese shipping and choke off China’s supply of crude oil.

Working in conjunction with the US Navy and US Indo-Pacific Command, the Indian Navy was able to avoid detection until after India and China had sat down at a summit to discuss China’s encroachments across the Line of Actual Control. Although China lodged numerous complaints about the Indian Navy’s presence in the Strait, they came to nothing, and China was ultimately forced to back down in shame.

India has since expanded their presence in the Strait, building far more in the way of naval bases and even going so far as to establish an air base where long-range attack aircraft can attack hostile shipping.

Bengal Famine

India takes the security and control of the Strait extremely seriously due to the events of WWII.

While most Americans are no doubt familiar with the joint US-UK-ANZAC operations in the Pacific which sought to defeat Imperial Japan one naval battle at a time, the events on the Asian mainland are often forgotten. We never hear about the green hell which was New Guinea or Burma, the great Siege of Singapore, or the Bengal Famine and the deaths of over 4 million Bengalis.

Bengal was already in trouble when the war began. Under Bengali law which the British Empire had left in place, absentee landowning aristocrats known as Zamindars and wealthy peasants known as Jotedars had been accumulating land by making loans to the Ryot - small or even dwarfholders with insufficient land to turn a profit - and sharecroppers known as Bargadars. With the Great Depression having erased most of India’s small agricultural banks, these wealthy land owners were the only option most peasants and sharecroppers had available to them.

Bengal was also highly dependent on river transportation, with few if any roads. British attempts to build railways in the area to provide safer transportation wound up disrupting many of these rivers and silted up several rivers which reduced the water needed to grow rice. To make matters worse, railway construction also created bodies of standing water where cholera, malaria, and diseases that targeted rice could grow.

These issues were already causing a minor but manageable food crisis - even with much of the Royal Navy busy in the Atlantic trying to keep Britain fed and in the war - when Japan took Burma.

Over a million Indians had left the British Raj before the war, working the Burmese rice paddies and sending money home to their families. This also went far toward making sure Bengal had sufficient food to keep everyone alive, as Burma was renowned for its fertile rice paddies. When Japan began bombing Rangoon in December of 1941, these Indian migrant workers left for India, seeking to avoid the much-publicized fates of the Chinese.

Merchant vessels kept running the route from Rangoon to Calcutta, braving Japanese commerce raiders, until the fall of Rangoon in March. By the end of April, Japan had sunk 100k tons of merchant shipping and had effectively thrown the Royal Navy out of the Indian Ocean. Seeing the food crisis developing in Bengal, local princelings shut down the grain trade to protect their people and the British Raj attempted to impose price controls in Bengal. With the expected result of shortages and the growth of a black market.

London and Washington were powerless to help due to the Japanese controlling everything between Ceylon and Midway, and storms and resulting outbreaks of diseases targeting rice only made the situation even worse.

And then the Quit India movement mobilized a general strike and what little there was of remaining commercial rail travel for the civilian supply chain ground to a halt. Widespread sabotage of rail and communication networks by Indian independence activists who viewed this as a chance to negotiate freedom for India only made the attempts by the British Raj to manage the crisis even more feeble.

4 Million Bengalis would die of hunger before the British Indian Army seized control of the civilian distribution networks and used their superior knowledge of logistics to ensure people were fed.

This nightmare has left a scar on the Indian psyche and driven home how important control over the Indian Ocean is for their very survival. A fact which no doubt shapes India’s aggressive response to China’s “String of Pearls” initiative to build an infrastructure capable of hosting People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) vessels in Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Bangladesh, the Maldives, and Somalia, with an anchor in the form of a naval base in Djibouti.

India has responded by bolstering investment in its Navy and forming closer bonds with the nations of the South China Sea and the nations which border the Strait of Malacca which is growing increasingly alarmed by Chinese imperialism in the region.

Pipelines

China recognizes the threat India now poses to their reliance on foreign oil, and has begun to take steps to protect against the Indian Navy engaging in commerce raiding.

As the PLAN is still largely a greenwater navy with short-range capabilities and likely won't become a true bluewater navy for at least eight more years - assuming the CCP is still in power at that point - China's ability to secure their supply chain is called into question at best.

Especially with the world's second most powerful navy sitting just across the East China Sea, and likely to have more freedom to act with the Liberal Democratic Party poised to amend Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution. Although the PLAN outnumbers the Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF), Japan's navy has a qualitative edge in terms of materiel, training, morale, and personnel. A situation made worse for China due to the fact the PLAN is still largely manned by conscripts and is as rife with corruption as the Russian Navy is.

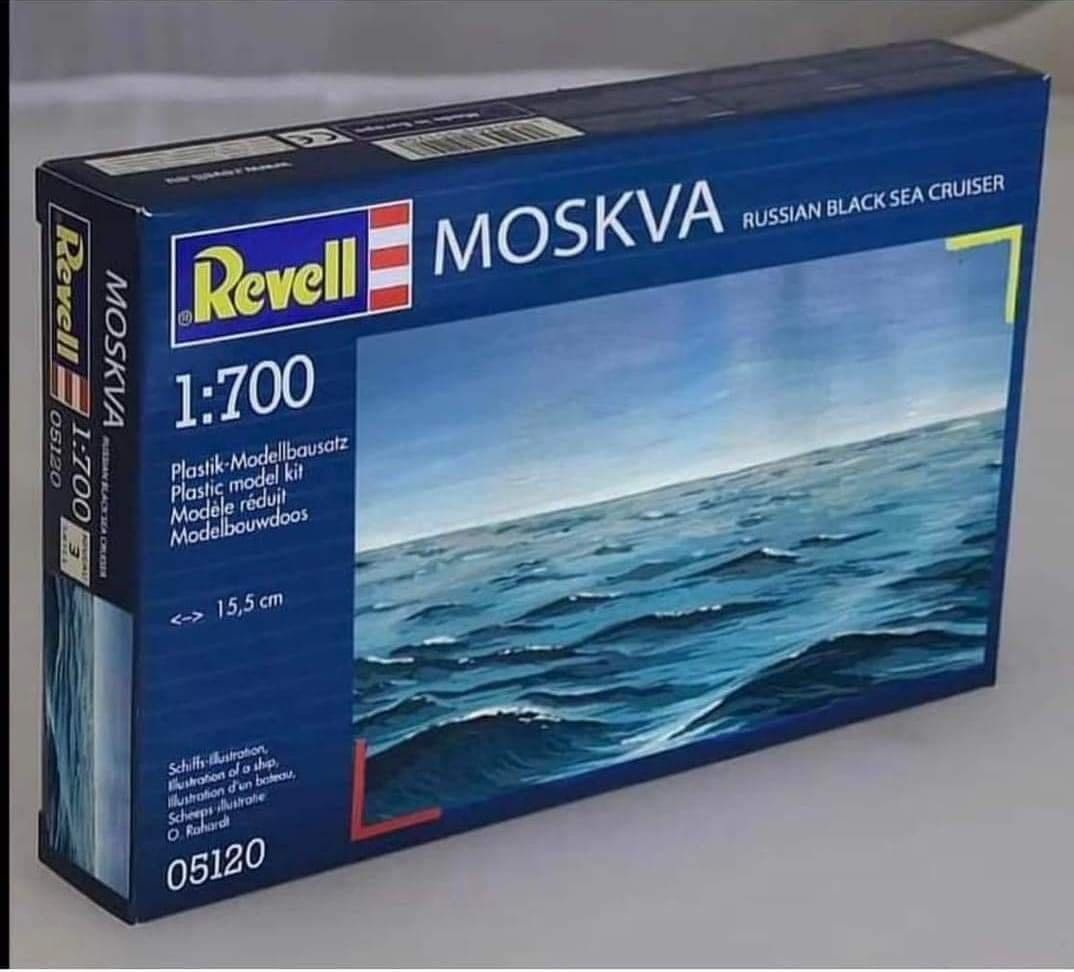

Just ask the crew of the Moskva how important those last two factors are

Its also worth noting that Japan has four aircraft carriers multi-purpose destroyers, all of which are operational.

This is in contrast to China’s carrier fleet, with the Fujian not expected to be ready to undergo trials until 2024 if everything goes well (it won't) and the Liaoning has only avoided going the way of its sister ship, the Kuznetsov, by spending most of its life in a drydock as a glorified theme park.

https://twitter.com/Sputnik_Not/status/1505957322870464516?s=19

Growing antagonism towards Australia, sparked by former PM Scott Morrison's request for an examination of the Wuhan Institute of Virology to determine if the COVID Pandemic began due to an accident in the lab, has also resulted in the Royal Australian Navy changing doctrine from regional security towards power projection. Perhaps the best example of this change in stance being Australia's decision to scrap a French-designed conventional submarine project in favor of US-designed nuclear submarines. This shift will enable Australian submarines to cruise further from support ships and project power to places such as the Strait of Malacca or even into the South China Sea outright.

This leaves them with four options:

Iran and Pakistan

Central Asia

Russia

Myanmar/Burma

Iran and Pakistan

-Afghanistan stuff goes here

For China, there is a severe temptation about Iranian oil. A fellow enemy of the US and a major producer of oil which can be purchased at a discount due to heavy US sanctions on oil sales, the problem for China has always been how to procure said oil without running afoul of punitive sanctions which could strangle China's ability to make up for their food shortfall. This has mainly been solved via tankers full of Iranian crude discharging their cargo into half-full ships with crude from other suppliers, where the crude would mix and China could claim the crude came from another supplier.

There is a natural solution to this in the form of a pipeline. And Pakistan is already acting to supply this solution.

Originally intended to connect Iranian natural gas fields to India before they later dropped out of the deal due to US pressure, the Iran-Pakistan Peace Pipeline will connect Iranian fossil fuels into the broader network of Pakistan's pipeline network. It will be hooked into the Turkmen-Afghan-Pakistani-Indian pipeline at Multan, and from there be hooked into the various pipelines which feed China.

This is good news for China in a number of ways.

The first is the least obvious. Thanks to former-PM Imram Khan, Pakistan has run up a significant debt with Beijing. To remedy this, Pakistan has turned to the oldest trick in the book for a colonized power to get out of debt with an imperial one - concessions.

China has managed to secure the contracts to build the physical infrastructure for the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor with the use of raw materials and finished goods produced in China and using Chinese labor. All with a 20-year tax holiday. This concession includes an extra-territorial town at Pakistan's port of Gwadar, a major highway to connect the port to Xinjiang, and a pipeline that will allow China to tap into the Pakistani network.

The second benefit for China is the natural one which always follows the construction of infrastructure in one's colonies, troop deployments. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor passes far too close to the Tribal regions which served as a stronghold for the Taliban and associated militants during our misadventure in Afghanistan, and for the radical Islamists who have been waging a low-intensity civil war with the Pakistani government for decades. Meanwhile, Gwadar is located firmly in Baluchistan, where nationalist rebels have begun targeting the Chinese for their support of the Pakistani government. This has given China the excuse to station a small contingent of PLA troops within Pakistan to protect their investment.

The third benefit is the most obvious. While this pipeline project cannot transport sufficient fuel to meet all of China's needs in case of a war with India, it can go a long way toward mitigating the issue. Especially given the radicalism present in the Pakistani government and its declared willingness to use nuclear arms against India should India try to invade.

And finally, you have the financial benefit. China will be loaning Pakistan the money used to pay China to build the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), placing Islamabad even deeper into Beijing's debt. And unlike African nations who have the benefit of the entire Indian Ocean between themselves and the bulk of the PLA, Pakistan has a land border with China and a hostile power next door that has pinned most of their troops in place. There will be no refusal to service the debt.

This latter point is driven home by the fact China has built a literal colony to house 500k Chinese nationals at Gwadar.

For comparison, that's the population of Omaha.

China has also opened negotiations with the Taliban to build a spur of the CPEC highway between Gwadar and Xinjiang to Kabul. Though we don't know where this road will pass, the most likely result will be China taking over the Khyber Pass Economic Corridor project originally planned by Islamabad.

However, this greater involvement in Afghanistan also opens them up to the threat posed by the ISIS franchise in Afghanistan.

Central Asia

Kazakhstan has been a vital source of fuel for China ever since the Kazakhstan-China Pipeline was completed in 2009. Capable of transporting 20M tons (140M barrels) of crude oil, it was the first inroad into former Soviet oil fields. That same year, China built another pipeline that ran through Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan to connect to the oil fields near the Amu Darya river in Turkmenistan to transport 55G cubic meters of natural gas to customers in China.

Though a small portion of Chinese imports, the two of them have served as a roadmap for Chinese relations and energy security. China has helped fund numerous other pipelines, all designed to mesh together into a cohesive network that can be used to supply their needs, at least in part.

However, these seemingly safe routes have been thrown into question.

Kazakhstan rose in rebellion in January and came close to toppling its government before Russia sent in a full division of paratroopers to kill 208 and arrest almost ten thousand more. Although the constitution was recently amended to reduce the power of the executive and strengthen the legislature, Kazakhstan remains effectively a dictatorship.

Uzbekistan recently erupted in similar unrest over attempts to curb the autonomy of the Republic of Karakalpakstan, inflaming tensions between Nukus - the capital of Karakalpakstan - and Tashkent. Officially a sovereign nation in a union with the rest of Uzbekistan, Tashkent was forced to scrap the changes to stop the rioting. However, the increased tensions and the knowledge they were able to use force to change policy in Tashkent combined with the damage done to Karakalpakstan by the continued draining of the Aral Sea and the rising price of food means the unrest could return at any time.

Without Russian paratroopers to put it down.

Then you have the Kyrgyzstan-Tajikistan Border clashes which could escalate and drag the rest of the region into a general war. A situation made worse by the outbreak of food riots in Tajikistan’s Gorno-Badakshan region and the brutal means used by the Tajik government to suppress them.

There is every reason to believe Central Asia is a powderkeg. One which may threaten Chinese energy security.

Russia

Ironically, China may be the only one to benefit from Putin’s folly. China has been in talks with Russia for years at this point to establish more energy links to deliver oil and natural gas to Chinese refineries and cut down on Russia’s dependence on European markets. Putin has resisted this, viewing pipelines such as Nordstream as a key method of manipulating public opinion in Europe in his favor.

While he managed to use the threat of cutting all Russian fossil fuels from the European market to weaken the French and German response to his invasion of Ukraine, it proved to be a far less effective tool than he thought. And what little effect it has had maybe shaped entirely by the fact the US Government has been captured by environmental activists and thus is incapable of producing oil in high enough quantities to counter the loss of Russian oil.

Russia has started talks about speeding up the construction of the Power of Siberia 2 pipeline which would link Russian pipelines supplying China already to the oil fields which supply Europe. Ostensibly, this would allow Russia to have Europe and China compete for the oil and, theoretically, drive up the price.

In reality, China is likely to be the sole purchaser until someone else comes to power in Russia. Just as planned.

Myanmar

Although Russia is the most stable link in the Chinese link, Myanmar may be the most important link.

It’s also the one I believe is most likely to blow up in China’s face.

As one of the few nations which border China and the Indian Ocean, China has increasingly looked to Myanmar as its key to avoiding the issues with the Straits of Malacca. The key to this shift is the new port on the island of Kyaukphyu, which has a large oil and natural gas terminal connected to a pipeline that delivers 12M barrels of crude and 12G cubic meters of natural gas to refineries in Yunnan every year.

China has recently begun negotiations with the Junta for additional pipelines to further expand capacity. The Junta is likely to grant the request due to the need for funds with which to fight the ongoing low-intensity civil war the Junta is facing. A war that is getting worse by the day.

A war which China has chosen to keep going by supplying both sides.

While the domestic and international politics of this civil war are too long for this article, the Chinese position can be best summed up as having been caught in a trap where their only viable plan is to maintain the current balance of power between the Junta and the various rebel groups to be able to continue extorting the Junta for security assistance in exchange for infrastructure concessions.

This will inevitably blow up in their face, which I will discuss at length in another article.

Next week we’ll look at the Chinese real estate sector, followed by the financial sector the week after, and then a look at China’s reliance on coal with an expansion on the issues China is facing in terms of water usage and contamination as a result.

A very informative analysis. I somehow missed this when it was published, but now I have discovered it. Thank you!